Groundbreaking Experiment Designs Cancer Cells Attack to Their Own Tumors

Yes, you read that right: scientists have figured out how to make cancer cells become traitors to their own tumors. Thanks to CRIPR genome-editing technology, a four-year study has made extraordinary headway as of Wednesday, July 11, discovering that human immune systems could potentially fight cancer on their own.

Ever since it was discovered 12 years ago that cancer cells return to the tumor after metastasizing in far parts of the body, many ideas of how to engineer these cells to work as assassins have surfaced. This new experiment conducted by Khalid Shah and a team at the Center for Stem Cell Therapeutics and Imaging at Brigham and Women’s Hospital could hold preliminary answers on how to progress on the seemingly impossible standstill of cancer treatment.

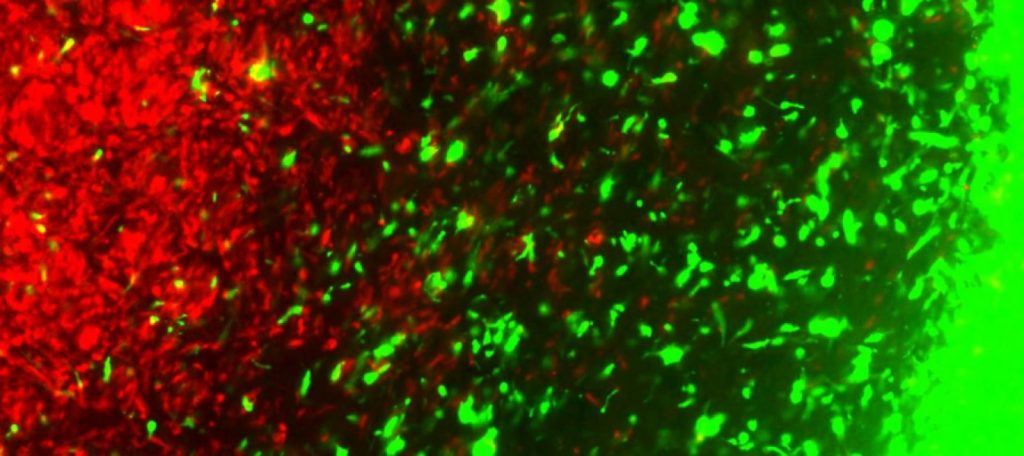

According to Stat News, Shah and his team extracted tumor cells from lab mice, and then used CRISPR to make those cells exhibit a molecule that triggers a “death receptor” on cancer cells, causing them to self destruct, on one group of mice. Science Daily reports that a second method of “ pre-engineered tumor cells that would need to be matched to a patient’s HLA phenotype” on a different group of mice. The team tested these assassin cells on three types of tumors: primary glioblastoma, the deadliest form of brain cancer; recurrent glioblastoma, where cancer that was treated became immune to chemotherapy; and breast cancer that had metastasized to the brain.

The team saw the mice with the primary or reoccurring brain cancer tumors’ shrink remarkably with 90 percent of the mice surviving weeks to months after initial treatment (these glioblastomas are usually 100 percent lethal to both mice and people). Half of the mice with brain metastases survived several weeks after treatment, which could mean that genome-edited tumor cells might provide therapeutic relief. The specially engineered tumor cells were made with a ‘kill switch’ that would kill them after they presumably killed the tumor.

As with most preliminary cancer treatment research procedures, some lingering questions remain, most promptly what happens to the farther metastases after the tumor is destroyed, since scientists only know rehoming cells to make a one-way trip back to the tumor. It’s the metastases that cause near 90 percent of cancer deaths, not the original tumor. Still, the study holds promising evidence that genome-edited honing cells could unlock a world of treatment for those with preliminary and reoccurring cancers. Shah is confident in the rehoming characteristics of cancer cells; he says it’s just “a matter of taming these cells to find the ultimate cure.”

Shah and his colleagues submitted their research to Science Translational Medicine 1 year ago, and he claims they’ve discovered even more about the CRISPR’d cells effects on tumors since then. “This is just the tip of the iceberg,” Shah says. “We think this has many implications and could be applicable across all cancer cell types.”