Mentorship Coordinator Serves Virginia Community 400 Children at a Time

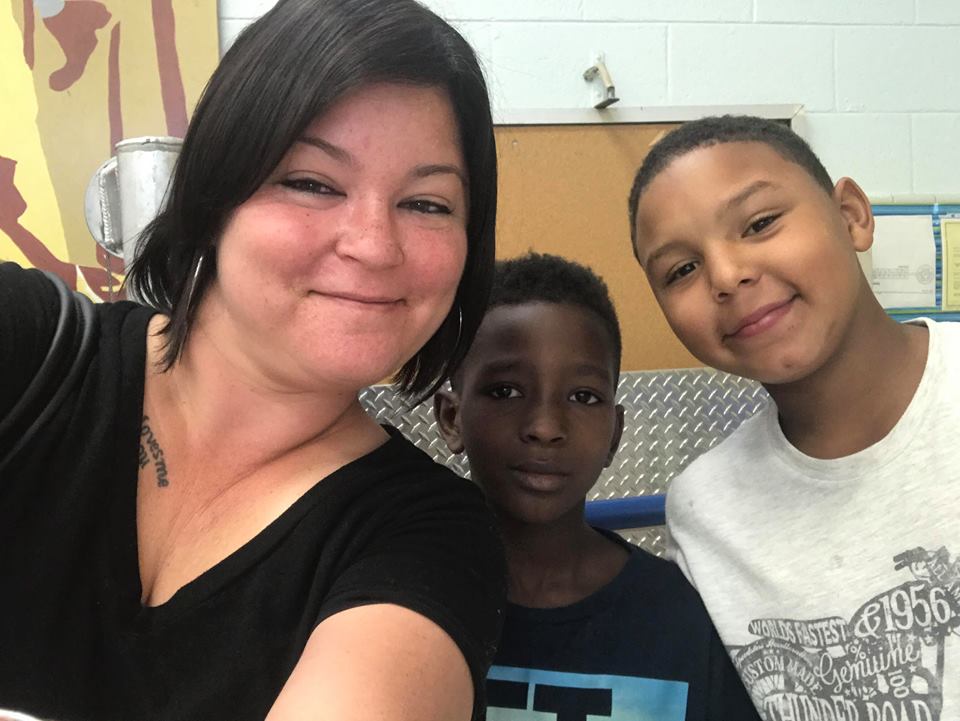

With no biological children of her own, it is common to hear Casey Rogers affectionately say “my kids” when talking about students at George Washington Carver Elementary. The students call her “Miss Casey” when they aren’t calling her “mom.”

“I feel like I’ve got hundreds of kids at the same time,” she told CMN. “I don’t feel like I’m lacking in any way other than having somebody that looks like me — and I’m good on that too.”

The 39-year-old is the Carver Elementary site coordinator for Communities in Schools of Richmond – a subset of a national program that pairs public school students with mentors of college age or older.

During her time with The Carver Promise, a program under CIS specific to Carver Elementary, she has applied her personal touch to the lives of children around the school for nearly two decades.

“She’s like the mastermind behind it all,” former student T.J. Thompson, 26, said about Rogers. “The only thing that really separates Casey from everybody else is she was really connected to everybody. She wanted everybody to do good.”

The Carver Promise has fulfilled their “promise” since 1991: all students in the third through fifth grades will be provided mentors. Rogers began her work with Carver elementary in 1999 as a mentor and has since been employed by the organization — and later CIS. The Carver Promise now extends to children in the first and second grades.

At a population of over 500 students, roughly 400 of Carver’s “peanuts” are old enough to be matched with a mentor; mentors usually are students recruited from Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Richmond, J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College or Virginia Union University. According to Rogers, Carver has nearly reached a 1-to-1 ratio of mentors to children.

Mentors visit their mentees for an hour once weekly and are expected to stay with the mentee throughout their time at Carver, unless the mentor graduates or is otherwise unable to participate any longer. During meeting times, mentors will typically take their kid down to the mentoring room in Carver’s basement where there are games, books and other activities to engage with.

Through CIS, Rogers and other coordinators not only match students with mentors, but also track student progress, facilitate resources for students with special needs, and provide college preparation assistance as the children move through the rest of grade school. According to Rogers, roughly 70 percent of students have improved their reading ability, partly due to mentors helping garner more of an interest in reading.

“That’s the most rewarding part is when you find and can identify a kid who wouldn’t have been getting those services if it weren’t for their mentor,” she said.

She said she has been matching mentors with mentees for so long that she can typically gauge a mentor’s character at their first meeting. Having been involved with mentoring for 19 years, Rogers has nearly gotten the process down to a science — which is why she had such ease assigning me a child.

—

The first day I mentored at George Washington Carver Elementary School was filled with uncertainty. Making my way down to the basement of the 67-year-old building, I dodged kids who were running to lunch and recess while the humid September weather hung idly in the poorly air conditioned hallways.

In the office next door to the mentoring room that was filled with laughter and games sat “Miss Casey.”

I attended the mandatory new mentor orientation the previous week – which had a turnout of about 100 college students and other adults from the community. When I met Rogers that day, it blew my mind thinking about how altruistic someone had to be to work with young children for as long as she had.

“Seeing when mentors teach their kids how to tie their shoes or something like that … it’s just like they’re going to remember that the rest of their life because of that person,” Rogers said. “I just think that’s cool.”

Since it was my first day as a mentor at Carver, I needed to be matched with a child. She asked me two questions: if I had a gender preference or if I had an age preference for a mentee. After giving my answer, only five seconds went by before she almost instinctively assigned me to a boy in the fifth grade.

I remember her telling me: “He talks a lot and he thinks he’s Chris Brown … but I think you’ll be able to handle him.”

She was right, and I have been his mentor for nine months. We meet for about an hour once weekly to do whatever he wants to do, which is typically lose to me in the card game UNO and show off his new outfits and shoes. He told me he had a different mentor before me who showed up once and never came back again, so I made it a goal to stick around for as long as I can.

Like most other students Rogers said she comes across, I just needed a place to get community service hours. Much to Rogers’ surprise, at the the end of the school year I asked if I could be his mentor at the CIS program for his middle school – since he graduated fifth grade last month.

My kid grew on me, much like Rogers says the thousands of kids she has come into contact with have grown on her.

Rogers herself was first introduced to The Carver Promise while fulfilling requirements for a social work class at VCU. She became a mentor to five kids her senior year of college before graduating with a degree in criminal justice.

Rogers decided to put off her long-held dream of becoming a police officer when the job became available upon her graduation. After securing a job with The Carver Promise, she never left.

—

Rogers insisted that she does not do her job for the cliche recognition of a white woman saving black kids. She said her primary motivation is always her kids.

“I can drive down the street and listen to Taylor Swift and they’re going to look at me a certain way – not realizing what I do for the black community,” Rogers said. “And I’m okay with that; I don’t care because I know what I do … I care what these kids think. I don’t care what anybody else thinks.”

Thompson praised Rogers for her kindness as a motherly figure to the community, despite her humility.

“I don’t even think she even thought about it,” he said about Rogers deciding to take him on a nearly six-and-a-half-hour drive to Bethany College in West Virginia, where she dropped him off for his freshman year. “She made sure I had everything straight.”

Natalie Lewis, another former Carver student, could also attest to the personal influence Rogers had on her life beginning nearly 20 years ago.

“Casey has always been supportive of my family,” Lewis said. “She came to my high school graduation and college graduation. My mom adores her and admires the work that she does and the relationships she has built with all her students.”

Rogers told CMN she often finds herself acting in a motherly role toward her kids. That is not to suggest that parents in the community are incapable of providing for their children — she said she feels parents in the Carver community get a worse rap than they deserve.

“A lot of our parents are overwhelmed,” she explained. “They’re trying to get up and out, … Their self-esteem is usually down because they don’t feel like they can provide a safe environment. It’s a whole bunch of B.S. that comes with poverty.”

Despite the B.S., Rogers said she believes that children who are motivated enough can have the willpower to uplift themselves and strive toward better futures when they become adults. Rogers, however, knows how it feels to see children slip through the cracks of society.

“Damnit!” Rogers said one day, hanging up the phone, slamming her hand down on her desk and startling me and my mentee.

Just like that, on an otherwise normal day in April, she received word that another one of her “kids” had been killed — shot dead.

“It happens all the time,” she said about losing children who she watched grow up – namely to senseless gun violence. “It’s not hard to tell who is following that path … I’ve seen kids that could’ve really been something and we had to bury them. That’s life unfortunately.”

Rogers said, however, that she cannot take any days off. The grief process is discouraging, she assured, but she said the day-to-day interactions with her kids are what keep her going.

“It’s just the little things that actually they do for me that they don’t even realize helps me want to still do it,” she said about her job.

“The difference that I have seen in the kids that get out [of rough neighborhoods] versus the kids that stay in is their own personal will,” Rogers said. “I think that it has to be something that they just do not want and they can’t make excuses for it.”

Thompson added that the mentoring program is “a powerful thing — the young kids need it because it’s an escape.” As a long-time Jackson Ward resident, Thompson said programs like CIS provide a respite from the often harsh reality the kids live in outside of school.

She explained that, although the mentoring program has its place in educational enrichment and providing good role models, the most important thing for kids is finding their own intrinsic motivation.

Lewis, for example, was the third child of four, and the first to go to college in her family. She said the mentors she had were her motivation to go to VCU. She is now a behavior counselor for children with autism, drawing inspiration from her experience with Carver mentors.

“Having a mentor definitely put a bright light on college and exposed to me the benefits of going,” she said. “It also opened my mother’s eyes to college & how great it is.”

Thompson attributes his successful path in life to Rogers and his mentors.

“I wouldn’t even be here today if it wasn’t for them,” he said. “Casey will just come around and she’s part of my family. She’s like a mother to us. I always think about what I do because of her.”

Rogers said she wants to see her students succeed, albeit she measures their success through how content they are in whatever situation they find themselves in.

“If you grow up and you’re a good person, that’s my [version of] success,” she said. “If you’re working at McDonalds and you’re happy [but] you’re living in the projects, I’m okay with it … As long as you’re alive — I know that sounds crazy.”

—

One of Rogers’ favorite aspects of providing children with mentors is that, at the intersection of four different universities, she said there is an abundance of diversity that mentors bring with them.

“It is important to have mentors that look like them and mentors that don’t,” she said, considering the majority of elementary school-aged children in Richmond are black. “Especially the mentors that don’t look like them [because they] are teaching them ‘this is where my family comes from’ or ‘I’ve been here.’”

There are several posters on the walls of the mentoring room. Some are of maps, while others have photos featuring people of different ethnicities and cultures.

Even I have had the pleasure of pointing out to my fifth grader where Pakistan – my father’s native country – is on the map. He of course had never heard of it, but I was nevertheless able to teach him something new that day.

“Everybody is not who you think [and] not what the news portrays,” Rogers said. “Every white person is not racist and every black person is not a criminal. It’s time for us to have these conversations with these kids.”

She said the experience is mutually beneficial for the mentors as well because it makes them “aware of the inequality and the issues that these kids face.”

“It’s unfair both ways to judge by race as to what kind of difference this person can make or what kind of impact they can have,” Rogers said. “I prefer a person to come to a school, get to know the kids, … and spread the word that these kids aren’t what you think they are.”

—

Communities in Schools was founded in the 1970’s in New York City and has sites in 2,300 schools – in 25 states and Washington D.C. – according to their website.

A full list of affiliates, or cities where CIS sites are located, can be found here.