Painter Jon McNaughton’s Novel Portrayal of Modern Conservatism

Jon McNauhgton

John Dyck, CUNY Graduate Center

In recent years, Jon McNaughton has emerged as one of the most well-known artists on the political right.

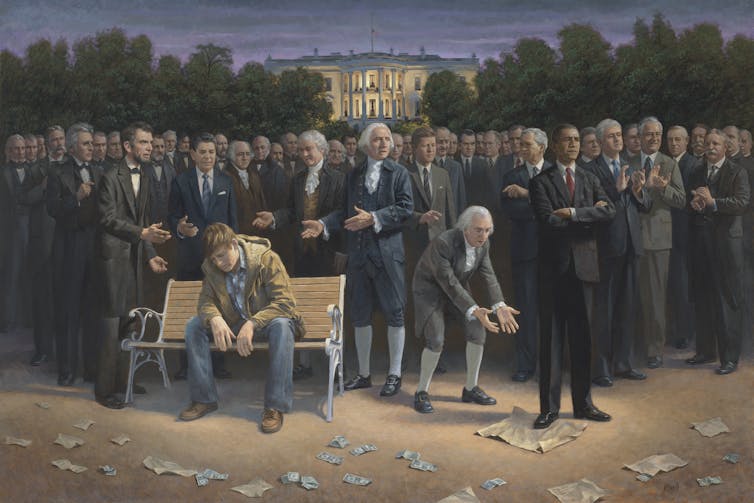

His 2011 painting “The Forgotten Man,” a not-so-subtle criticism of Barack Obama, became famous when Fox News host Sean Hannity bought it after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election.

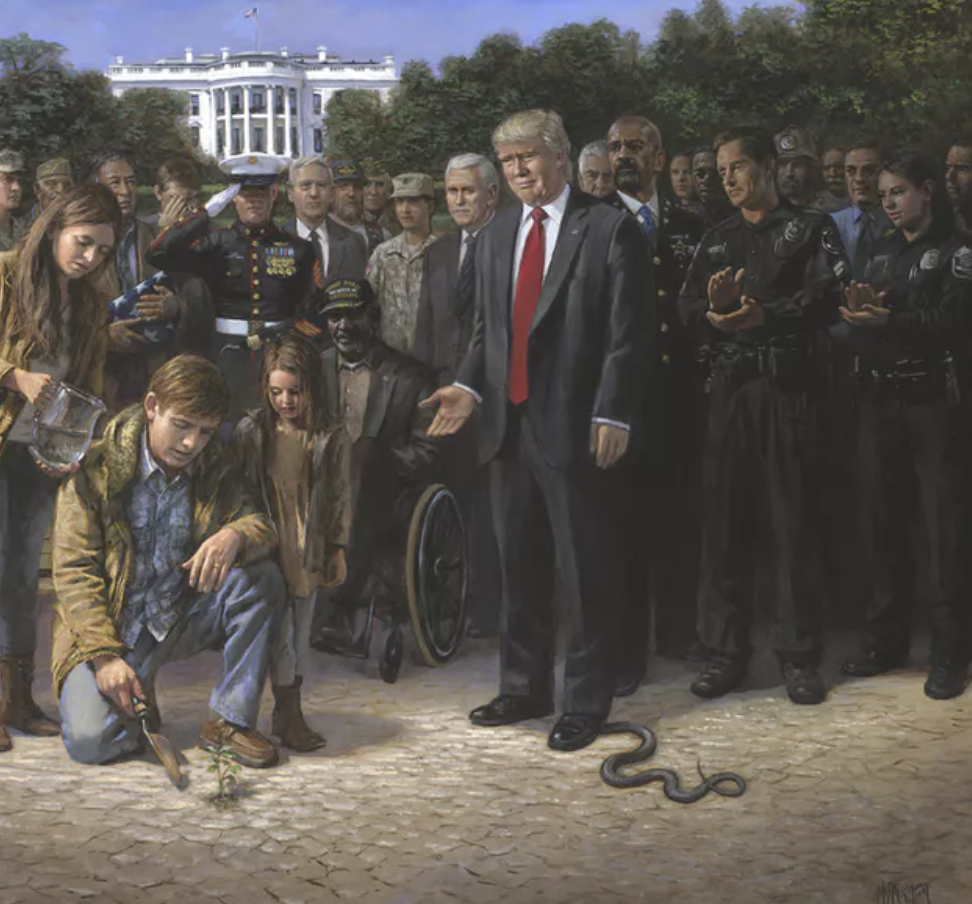

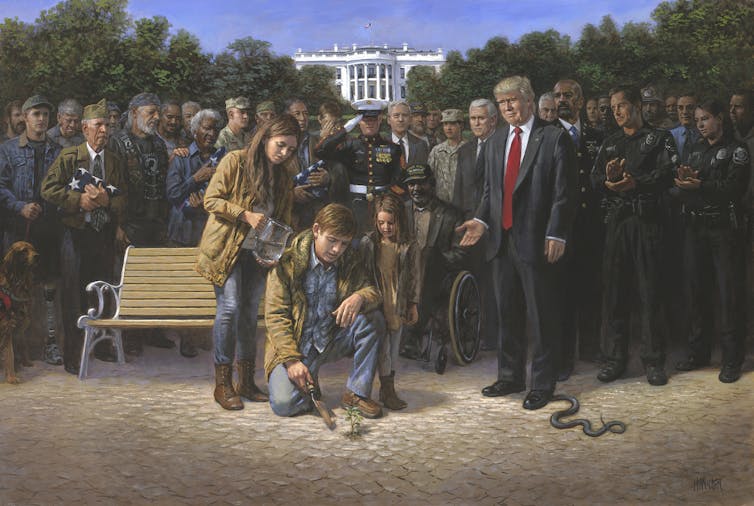

A longtime champion of McNaughton’s work, Hannity promoted a more recent painting, “Respect the Flag,” when McNaughton unveiled it in February of this year.

The painting, which depicts Donald Trump standing on a football field clutching a tattered and dirtied American flag, elicited giddy ridicule from Trump detractors and strong praise from Trump supporters.

McNaughton himself has recently admitted that he’s “a little perplexed” at how well his paintings are selling. Yet there’s clearly something about them that resonates; people love to talk about his art, whether out of hatred or love.

What’s so special about McNaughton’s work? As a philosopher of art, I wanted to explore what makes McNaughton’s work distinctive from other political art on the left and the right.

McNaughton’s allegorical style

As political artworks, McNaughton’s paintings are firmly realist: The political message here makes explicit reference to its subjects. Each has an well-known icon, whether it’s a president, historical figure, the American flag or the Constitution.

There are many works of political art that don’t make explicit reference to their subjects: Consider Nam June Paik or Ai Weiwei, whose works are meant to explore political issues without using realistic depictions.

Other artists on the right, such as Steve Penley, also depict iconic political figures. But Penley’s work is not allegorical the way that McNaughton’s is. Instead, Penley portrays icons in a straightforward way.

Steve Penley

With McNaughton, the icon often represents something, and each of the paintings contains a barely veiled allegory that sends a crystal clear message. We know exactly how McNaughton feels about his subjects; each figure is instantly charged with moral significance.

Barack Obama stepping on the Constitution represents his supposed abuse of the Constitution. Meanwhile, Trump’s attempt to clean the flag apparently represents his supposed respect for the national anthem.

Jon McNaughton

McNaughton’s works are also packed with many little references.

Journalist Marian Wang wrote of McNaughton’s “One Nation Under God” that “the details and symbolism here are impressive and painstaking.” Look for a long time, and you’ll be surprised to find new details charged with meaning – just like, say, Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.”

Is directness a bad thing?

Nonetheless, to many art critics, McNaughton’s work seems derivative and cheesy. The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl writes of “The Forgotten Man” that “the bathos of the scene practically cruises for ridicule.” Art critic Jerry Saltz says that McNaughton’s work is “typical propaganda art, drop-dead obvious in message,” and “visually dead as a doornail.”

There might be a lot of details, like Bosch, but the analogies are clearer in McNaughton’s paintings – and more clearly charged with moral sentiment. Saltz’s complaint is that the messaging here is too obvious.

Does the clarity make it bad?

Political art is often praised for being direct. Look no further than Keith Haring’s activist work. Or consider Leo Tanguma’s “The Children of the World Dream of Peace.” These pieces seems to share a clarity and obviousness with McNaughton’s work.

Mike Knell, CC BY-SA

So McNaughton’s themes might be obvious, but that’s not enough to make it bad. Perhaps, as Susan Sontag once suggested, critics like Saltz suffer from a partisan impulse when they complain about its directness. Or perhaps the critics are not complaining about the clarity exactly, but the tawdry imagery and too-easy literalism that is peculiar to McNaughton. Though it seems this criticism should then also apply to Tanguma’s “The Children of the World Dream of Peace.”

In any case, the directness of McNaughton’s work can’t be the only reason that it’s intriguing, and his critics might be missing a central aspect of its appeal.

Tapping the well of grievance

McNaughton’s work evokes religious paintings (think of white evangelical art, like Warner Sallman) or patriotic art (think Steve Penley’s work or classic North Korean propaganda art).

But there’s an apocalyptic element to McNaughton’s work that doesn’t occur in either white evangelical art or patriotic art. Both evangelical and patriotic artworks have an optimistic bent to them – indeed, patriotic art is almost always fiercely optimistic. With some exceptions, like “Teach a Man to Fish,” McNaughton’s work tends to be characterized by a deep pessimism.

In his analysis of conservatism, “The Reactionary Mind,” political scientist Corey Robin presents a novel view about conservatism. To Robin, it’s not primarily a view about capitalism, a view about freedom or a view about rights. Robin argues that at its heart, conservatism is the view that traditional power relations should be maintained.

Robin claims that conservative arguments are often motivated by feelings of aggrievement and complaints about what has been lost. This happens when progressive causes are advanced – when same-sex marriage is legalized, for example, or when abortion is legalized. According to Robin, whenever equality is gained by some groups, other groups lose privilege. Conservatism frequently involves complaints about this lost privilege.

Loss is central theme in many of McNaughton’s works – loss of the Constitution, loss of respect for the flag, or loss of whiteness in politics. The crestfallen figures in “The Forgotten Man” and “Respect the Flag” seem to embody this loss, and it reflects the increasingly lost privilege certain Americans, whether it’s white evangelicals or the elderly, might feel.

Robin also argues that – despite its apparent frustration with the language of the left – conservatism often adopts progressive language for its own purposes. For example, conservatives often complain about “intellectual diversity,” claiming that the supposedly tolerant left does not tolerate conservative ideas. Notice, however, that conservatives, in making this argument, are using the progressive language of diversity.

Similarly, McNaughton’s work co-opts certain themes of progressive art to suit his own conservative purposes. A prominent theme in political art on the left is a kind of bleakness, or darkness. Consider Nancy Spero’s “Search and Destroy,” Diego Rivera’s “The Uprising” or Goya’s “Third of May, 1808,” each of which depict grim moments, from rape to execution. Likewise, McNaughton’s work depicts Obama’s presidency with a darkness that is usually absent in politically conservative art.

![]() Whether we’re motivated by love or by mockery, part of our interest in McNaughton is the paint-by-numbers interpretation, and the fact that there are many small tidbits to search out and interpret. But the darkness and the sense of loss help to make McNaughton’s work especially unique. Perhaps unwittingly, McNaughton deploys classic tenets of conservative rhetoric in an original artistic context.

Whether we’re motivated by love or by mockery, part of our interest in McNaughton is the paint-by-numbers interpretation, and the fact that there are many small tidbits to search out and interpret. But the darkness and the sense of loss help to make McNaughton’s work especially unique. Perhaps unwittingly, McNaughton deploys classic tenets of conservative rhetoric in an original artistic context.

John Dyck, PhD Student in Philosophy, CUNY Graduate Center.This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.